| CLICK on Thumbnails to see larger Image

The house in its original state

General View from the Rear

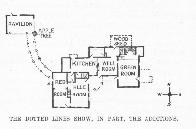

The House Plan

House as Completed

West end of House as completed

The Webster Porch

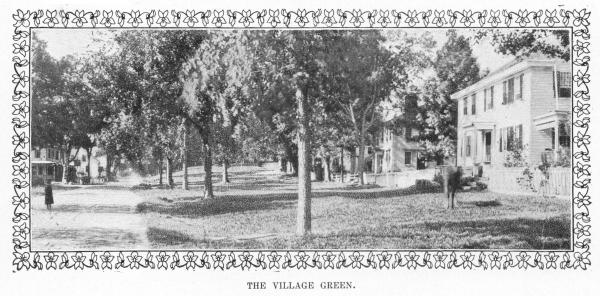

The road before the house

Dining Room, East End

A Bedroom NOTES: This article appeared in a 1901 issue of

CENTURY Magazine.

The house was later sold:

Click HERE

for a link to an article which details further information.

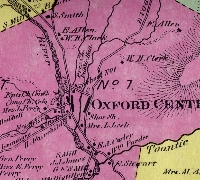

The mystery is not yet solved -- is the house still standing? If anybody knows, please email the Oxford Historian Where might the house have been located? From the narrative one might get the impression that the house was near the center of Oxford. The writer also refers to being on a hill. Below is a thumbnail of a map of Oxford Center in 1868. Click on it, to see where you would guess the house was located.

Now look closely at the image of the House as seen from the rear. The picture below is linked to a much larger file (3 MEGS) in which one can discern a white spire in the distance between the house and the boulder. Click on the image below for the larger view.

If the spire was, in fact, the spire of the Oxford Congregational Church, the white building that is visible to the left of the spire would have been the Old Masonic Hall, which was used as a Post Office, Town Meeting Hall, General Store, and for a time, as a school, in addition to serving as a Masonic Hall. |

In the meantime three most important

new means of transportation have come in, and will have an effect on the

cheap farm and on living in the country. The first of these is the trolley-line,

which is extending rapidly on all sides. Every foot of it serves as a station

and a point of departure to great sections of land lying within its sphere

of influence. The second is the bicycle; and the third, still in early infancy,

and probably destined to be the most important of all, is the automobile. When I begin, "In the meantime," I intend to refer to some articles I wrote in THE CENTURY MAGAZINE in 1894, describing a journey of investigation in the previous year among the so-called "abandoned farms" of Connecticut and of upper New England. I made that journey not merely as an observer of economic conditions, but with a keen personal interest and a desire to purchase. If, as I trust, those articles are not entirely forgotten, it may be remembered that I did not buy a place. The farms were not "abandoned," though they were often cheap, and many were charming; but a host of difficulties arose in the way. The main one was that those that were really cheap were from four to ten miles from a railway-station. To reach them and also to circulate with ease when settled, you would either have to hire a conveyance, which is expensive, and not always feasible at any price, or you would have to buy a horse of your own. By either plan you would add largely to the cost and difficulty. But the redemption of the cheap farms for summer homes is to be looked for from persons of small means; the wealthy can pick and choose at their will. I abandoned my search and had acquired the habit of going without an abandoned farm. Yet I am, for the last three years, the owner of a country home which has proved a most attractive and satisfactory one. What has happened? How account for this change of mind? One of the new means of locomotion has happened, namely, the bicycle. The bicycle, possibly now itself declining, to give place to something still more efficient, has deserved well of some millions of us, and we should rise up and call it blessed for all the pleasure and profit it has given us. There may have been bicycles before 1896, but for me they began to exist in that year. When my family and I had mastered this swift new conveyance, the problem changed its whole aspect. I saw that it was feasible at last to have a country home. Distance from a railway-station was practically abolished. Our own station at Seymour, Connecticut, for instance, three quarters of an hour by train from New Haven, and a couple of hours from New York, is something less than five miles from the farm. I make that in forty minutes, going up, as it is a steady rising grade, but I come flying down in twenty-five minutes. The convenient little steed is always ready for this, or for running to the village store and other errands. For heavier work there is a daily stage, or an occasional team can be got from the neighbors. The final selection of the farm at the pretty village of Oxford, on the road north-ward to Southbury, Washington, and Litchfield, was still another instance of the truth that what we seek far afield is often best found near home. The excursion in which I found it seemed almost entirely purposeless and vagrant, yet it was apparently preordained to this end. One delicious day in spring I obeyed that impulsion which especially drives us forth to nature at that time, and rode up a small valley I had not visited before. Following all the way the noisy, dashing brook, I came to a rural hamlet with a green village street, a couple of stores, a couple of inns with swinging signs, two churches, and a handful of white houses. At the Episcopal church a wedding was going on, and the bright, pleasant bustle of this ceremony added to the attractive impression of the place at first sight. I rode through the village to the top of a rise a little beyond the center, and there paused to look back upon the white spire which forms the central point in the composition of the charming local land-scape. This was Oxford. I had not then heard of it, and it has not yet attracted the summer visitor, but it was once more prosperous than now. Half a century ago a resident authoress wrote of it, from the top of a neighboring hill: "The picturesque village, the bold uneven ridges that shut it in, with all their depth and varied hue of foliage, their slopes checkered with green, waving fields and dark, furrowed ground, the little pond silvery with the rays of the setting sun, make a beautiful picture." At my right, by two large maple-trees, and above a terrace wall, was a weather-beaten house, with a lot of outbuildings, near by a wagon-shed of ancient red, and beyond this, up the sloping land, a fine, immense gray boulder, weighing perhaps three hundred tons. The name of "The Boulder" was already found. No other could be considered for the place. I entered, and was received by a pleasant-faced matron rocking in a chair by a south window. She had rocked there forty years or more, probably without anything so exciting happening as what happened now. Though the place was not for sale, she was persuaded to sell it to me. After a month of negotiation, I became the owner of that house, a barn in excellent condition, seven or eight acres of land, some old-fashioned furniture, and a real grindstone, some real pitchforks and scythes. Do you know, there are no end of people who talk most beautifully about a country life, and yet would not make the slightest effort to obtain it. If they do plan for it, they must have all their conventional belongings and their usual associates about them, and must settle only in some place already adopted by public favor. I note in the Massachusetts catalogue for 1900, for instance, that, out of the hundreds of farms advertised in the previous edition, only thirteen have been taken up for summer homes. This, of course, was before the new means of locomotion had developed to their present extent, and perhaps we shall hear a different account in the near future. In passing, blessings on the head of the bright, amusing Elizabeth, she of the recent " GermanGarden"! Her writing ought to do a great deal of good. She knows that nature is a well-nigh, all-suffi-cient friend, and how unnecessary a great deal of all the rest is. A diagram shows the irregular disposition of the house and the leading additions to it. The latter, shown by the dotted lines, are principally porches; we threw out no less than six of these, each with a comfortable bench. The first step was to set up that in the angle of the south, or main, front, and make there the principal entrance, uniting in one motif, as the architects say, the house with the sheds and wings. Disinterested local advisers counseled me to tear down all those sheds, as unworthy of the destinies of the place. So, too, others advised cutting away the "brush" that forms a beautiful natural screen, chestnut, maple, birch, hazel, and wild cherry, all round the land; and they offered to blow up for me the cherished boulder, charging only for the necessary dynamite, and putting in the labor at a specially low figure. There was a minor entrance in that angle, darkly hidden under a rampant grape-vine, which had grown so unruly and heavy that it was loosening the very corner-boards of the house. The formal entrance of the front was then suppressed, the ground cut away there a couple of feet or more, to give a pleasanter slope to the dooryard, and a little balcony was thrown out. A good large dormer-window was built, some ornamental railing of the primitive X pattern was extended along the roofs, blinds were hung at the windows, and the building was painted colonial yellow. The local critics began to show us a measure of favor. They admitted, as they drove by in their wagons, that they would not have believed the old place could have been made to look so well. As the work went forward, I photographed the house in its various stages, so that I have a complete pictorial history of it. Yet I was in such a hurry to get to work that I did not take it in its original condition, and I have nothing to represent it as it was at that time but a hasty, yet pretty accurate, note-book sketch. Dim and far away already that period seems. I spent the first night alone in the old house, to be on hand early to meet the carpenters. I arrived after nightfall. Not having any candles at the country store, they lent me a small lamp; but I lost the chimney in the shrubbery at our door, and had to go to bed by the brief gleam of its flaring wick. All night the tree-toads sent me their somnolent buzz, and the brook its hollow roar, while the lilac-bushes scratched and tapped the window-panes. We do not believe in ghosts, of course, but ghosts should avoid the very appearance of evil; they should not even pretend to exist. But oh, the beautiful bright morning that succeeded this! What a compensation was that fragrant morning of midsummer, dawning in the midst of a lovely prospect upon me, ready to begin at last that rural experiment which I had so long desired! It is a good sort of pleasure to try and build a picture instead of painting one. Much of the actual work I did with my own hands, partly because I liked it, and partly because of the difficulty of getting labor. The only mechanics in such communities are farmers as well, and they want to put you off till they have hoed their corn, got in their hay, or the like. And when they do come, they try to do the work in their own way, and are inclined to be cross and grumpy if you want to have it done in your way. Within the house the first proceeding was to knock out partitions and make larger rooms out of small ones. The parlor and a bedroom were thrown into one, and a pair of columns concealed the place of junction. The upper story could scarcely be said to exist for purposes of occupation. By throwing two stuffy bedrooms together, a fine large one was created, extending the length of the house, and, though the roof is low, it is cool, through cross-drafts, even at midday. At night, amid such hills, the temperature goes down rapidly, and you always expect to sleep under blankets. We brought up old-fashioned things from the city, and these, together with the brass-handled chests, and so on, that we got with the purchase, give the house a set of furniture in keeping with it. We have named various rooms, after the color of the wall-paper and stuffs in them, the "Blue Room," the "Red Room," the "Green Room." The Green Room is our dining-room when we dine indoors. It takes the whole interior of a wing, and has a long Dutch window. Some say it was anciently a kitchen, others that it was a cooper-shop. Its floor was entirely broken down, and we found it in use as a woodshed. It has a fine big chimney with generous fireplace. This made it worth while to redeem it. The chimney, sinking down as if overburdened with age and memories, was braced up with stout iron straps. A wooden cornice now belts the room; the massive posts were treated as pillars, and a window-seat and book-shelves were put in, but the brown timbers of the roof were left untouched and open to view. On one side has been evolved a paneled and pilastered gallery; at the end going up to a servant's chamber, over the well-room, there is a little green stairway, the balusters of which are made of bits of scythe-handles, with a sort of Louis Quinze effect. These are whims one can permit himself on an old farm, for he works in a material that he cannot harm very much, even if he does not improve it. Out of its eastern door is a lovely stretch of ground, with the path by which we may go to the village within our own domain, and close in front a fruit-tree quaintly named the " Sunday pear-tree," because it was set out on a Sunday. There are two wells of excellent water. These and the sanitary arrangements were carefully looked after, the rubbish that cumbers a farmer's yard was cleared away, and the weeds about the house were replaced with grass. We do not desire any formal paths; the grass grows up to the very door-steps on all sides. We raise some hay and a few flowers, but nothing else; it is easier and cheaper to let the neighbors provide the rest. They bring vegetables, chickens, eggs, butter, and milk to our door. While the earlier improvements were in progress we occupied a building which, from force of habit, we call the barn. But, as we depend on our bicycles, we need no real barn, and this has been turned into a studio or general play-house. The hay was all removed, and a balustraded gallery was set up at the level of the upper haymow, large enough for two beds, while there could be more below. The interior is in Venetian red, which makes an excellent background for decorative odds and ends. When the great door is rolled back, the large room is almost a part of the general out-of-doors, and has a particularly fine view upon the orchard. The latest porch to be added, transferring the main entrance to the west side, was the "Webster Porch." We feel that it may have had a deal to do with the preparation of Webster's Dictionary. I brought it last summer from an old house in New Haven, pulled down to make way for Yale University. The old house was once occupied by the poet Percival, who worked on the dictionary. Webster used to visit him there. If there had been no such porch, might not Webster, waiting in the rain for his knock to be answered, have been carried off by a fatal cold? In short, how do we know there would have been any dictionary? The porch fits its present situation like a charm; you would say it had always been there. I made mention at the beginning of a red wagon-shed. Just as the barn is no longer a barn, that red wagon-shed is no longer a wagon-shed; it is a pavilion, an out-of-door dining-room, and one of the chief sources of our comfort. A pergola, or arbor, of white columns, honors its new dignity, and joins it to the Webster Porch. One of its corner posts is a huge, spreading apple- tree. The apples from that tree casually try to drop on your head as you walk out to dinner. And, then, in the still depths of the night, they will come down on the shingles with a bang, sometimes a couple of them close together, roll weirdly along the roof, and land with a thud in the garden bed. It wakes you up with an alarmed sensation, and then you smile at the humor of it and go to sleep again. We take our repasts there all summer long. The road is hidden by a stone wall; in front, beyond the brook, rises a fine wooded hill; there is nothing in sight but the stone wall and the expanse of exquisite, reposeful green. We are some five or six hundred feet high, and this hill is, say, three hundred more. On a blasted tree on the top an eagle likes to sit, and we watch his motions, and wager as to when he will fly away, and on which side. I say "eagle," though some of us argue that he is only a chicken-hawk. They wish to go up there to the tree and try to find his nest, and determine the matter. But I see no use in this. When you have an eagle sitting on a blasted tree to amuse your leisure, why not be satisfied with that, and let well enough alone? We adapted the boulder to its new environment by building a staircase up one side and a platform on the top, while a table and bench below make it a comfortable retreat for the afternoons, when the sun is behind in the west. We could not forbear, too, aiding its druid-like, prehistoric air with a rude altar and some inscribed monoliths. The illusions are the only power in human affairs strong enough to keep us well going. May we not, therefore, claim some merit for creating this illusion of antiquity, and putting a prehistoric ruin just where one ought to be? Fortunately, the land in general needed little done to it. It was a question, rather, of trimming out superabundant plantations than of adding to them. Natural hedges run around all our boundaries and along the old walls, dividing off the fields, and most of them are full of roses or wild blackberries, raspberries, or grapes. An upper field abounds in strawberries. The wild grapevine occurs in extraordinary luxuriance; it swings from tree to tree, and the air is redolent in springtime with the delicate fragrance of its flowers, and in autumn with that of its fruit. At one place it spreads all over the rocks and the hollow of an old cellar with the look of rolling waves of green surf. Elsewhere it has completely overrun a clump of quince-trees, so that it was only necessary to cut out one side of the combination, and set a prop or two, to form a commodious bower. It would be difficult to find a greater variety of scenery than we have in so small a number of acres. I should almost have been content with only a single one of these views, We travel by going to one after another of them in turn. We have the front lawn with its maple shade and the brook; then the park-like vista eastward from the "Sunday pear-tree"; then the orchard westward—a real orchard, with all the charm in which apple-trees abound, from the blossom to the ripe fruit. Down in one corner of this is a miniature glen, with cliffs and a carpet of cool, delicate ferns. Then there is the boulder and its thickets, and higher up, in another field with cedars and more apple-trees, is the " Boer Kopje," a great cairn of stones (piled up by some long-forgotten resident), peeping forth mysteriously from embowering shrubbery. On the top of it has been fashioned a rude round-tower, and kopje though it may be, its boy commander flies the American flag, and has already sustained there more than one lively period of attack and defense. Over that way one has only to step across our wall to enter the thick natural wood that borders us. There is a bit of romance connected with that wood, too; the belt of it next us is an abandoned road, which, a hundred years ago, led over hill and dale, giving access to dwellings the very cellars of which are now untraceable. I shall touch briefly on the practical aspects of the case. I had feared at first to have to spend half my time hurrying to the market-town to provision the family, and I thought it worth doing even then. But, quite to the contrary, the housekeeping has proved to be even easier than in town. This is much due to the daily stage. Though a lumbering, slow conveyance for travel or for bringing out one's friends to the farm, it is a capital resource for procuring supplies. We signal it by a blue placard swung out of the window, and it stops under our maple- trees by seven in the morning. The amiable driver takes a prepared list, and he is back again before noon, bringing, say, meat from the butcher's, and of excellent quality, too, even by town standards, fruit and confectionery, a new broom and some cotton cloth for the servant, embroidery-thread for the mistress, light lumber and cans of paint for this deponent, and a drum for the son of the house. For such miscellaneous shopping his own charge is about ten cents. The stage- driver is the Mercury, the special providence, of the dwellers all along his line. An old woman awaits to give him huckleberries to sell, another hands up an old saucepan to be soldered. The complete history of one of his trips would make an instructive and amusing compendium of rural existence. Besides this resource, other butchers, bakers, fish-men, and fruit-men, too, drive by, on certain days of the week, jingle their little bells at our door, and await our pleasure. The servant question is often alleged as one of the drawbacks to a country life, but here again, judging from our experience and observation, we are obliged to think the dread is exaggerated. Our own domestic has followed our fortunes throughout. "Nora" has plenty of merits, to which I here gladly pay tribute, but she cannot be greatly different from her kind, and yet, so far from being discontented or "lonesome," she shows and declares great satisfaction with the new life and with the respite from that of the city. She likes to compare the way things are done here with that at her farm-house home in Ireland (to the great advantage of the latter). It is a pleasure to see Nora cruising down the shrubbery, popping ripe raspberries into her mouth, or sitting in the orchard with her lap full of apples; and if the kitchen fire were not so hot, though the next time I am going to try one of the patent stoves that go with oil or gasolene, she would get as much benefit out of it all as the rest of us. Thus far an epidemic of good health has prevailed among us all, and we have had no doctor's bills to pay. Our fellow-villagers have not been unduly excited over our arrival as the first summer-resort people in the region. I judge they do not greatly admire our taste for the quaint and old-fashioned in building and the genuinely rural in nature, but look upon our proceedings as rather eccentric and whimsical. Perhaps they will like it better after a while. The thing is good in itself, and our influence may linger after us, as they say the light of certain stars continues to arrive at the earth long after these themselves have been blotted out. This community, to be quite perfect, should have some of the defects of larger communities. It is a little retired and lacking in social resources; but, of the two evils, too little companionship is far better than too much. Our experiment has been an unmistakable success; the life is agreeable, it is healthy, and it is cheap. You have noticed that the one conclusion reached by nearly all persons who have passed their summer at the usual boarding-house, hotel, or hired cottage, is that they never want to go to that place again. We do not say that and we do not think it. We keep the farm much in mind in the winter-time, we talk it over with pleasure, we recall how we used to watch the birds there, and the fireflies, and those larger fireflies, the stars, and we are anxious to get back to it at the earliest moment. A large movement in farm-places goes on in those rather near the towns, which do not figure much in the official catalogues above mentioned. A multitude of lesser business men cannot get away for long vacations, and they must have something near by and easy of access. Indeed, there is no reason for the customary going away to great distances. The difference between city climate and country climate is immense, and almost any change from the city is enough. It is a point in favor of our purchase that it is so near by. We can run up there easily to spend the day and see how it is getting along. Still, the first enthusiasm having worn off, we do not do that as often as we had expected. The house having entered upon its long hibernation, all the homelike small objects are put away, the windows are nailed up, and draperies tacked over them. There is a chill within, and one does not want to spend half one's time in letting in air and sunlight and making fires, and then putting all back in winter shape again. We go up, of course, some days in the autumn, and an excursion or two there in early spring is particularly delightful, but the real satisfaction is that we can begin to live there so early in the summer. The hegira is made in the opening days of June. That is a delightful moment, indeed, the first glimpse of the country home again, left so many long months standing silent and vacant. It is like the palace of the Sleeping Beauty in the wood. The grass is knee-deep about it, up to the very sills of the doors. The first thing to do is to take a sickle and cut a way through the high grass, as one would cut paths through the snow in winter. And the slopes in the orchard are as white with daisies as if with real snow. Such is what one of the improved methods of transportation has done for us. As they become more common, they must influence immensely the filling up of the farms with summer residents. Perhaps, indeed, the next step may be a general scramble for these farms, and the call upon those who have not read the signs of the times, and seized the occasion by the forelock, to pay much higher prices than those that have hitherto prevailed. We won our country home, so to express it, by the bicycle, but we rather expect to have to hold it by the automobile, unless it be by the trolley, for already they talk of a link to connect the two systems above and below us. Why-will not some one bring out a motor-carriage, for two persons,—and a third light one at a pinch, —costing not much above two hundred dollars, and capable of being stowed away in small quarters? Such a conveyance is bound to come sooner or later. Why not give it to us sooner and not later? |