Chauncey JuddDavid Wooster's

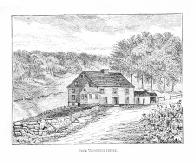

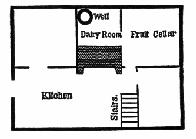

It was one of those large, old-fashioned mansions, of which a few remain to this day, capacious enough to meet the wants of the patriarchal households of those times, and to afford room for the spinning and weaving, the brewing and baking, and dairying connected with an extensive farm. It was situated on the eastern side of a broad, deep ravine, through which runs a small tributary of the Longmeadow Brook, upon the road leading from Gunntown to what is now Middlebury. Underneath the house was a large basement kitchen, and a cellar, divided into several compartments for storing fruits and vegetables, and the long rows of cider casks, large and small, supposed in those days to be as indispensable as the beef and pork barrels to the sustenance and comfort of the family through the winter. Behind the big stone chimney, in the space between

it and the outer wall of the basement, was a small

apartment, originally designed as a dairy-room, containing

a deep well, which supplied water to the rooms

above by buckets suspended from the ceiling and descending

through both floors. A dim light was admitted

by a few panes of glass in the outer wall. This room

was separated from the other parts of the basement

by brick partitions, and entered only by a door opening

outward into the fruit and cider cellar, which in

its turn was entered from the kitchen. It had a stone

floor, and was evidently constructed for the purpose

of being kept cool and dark, for the storage of the

milk, butter, and cheese of the dairy. I may add

that in all essential respects it remains the same to

this

day, except that the well is now covered, and the

room appears only as one of the ordinary apartments

of the old cellar. Mr. Wooster, having been apprised by the early visit of his son of the coming of the party, and not wishing to expose them to the notice of his numerous family, or of any chance caller or passer-by, had built for them a fire in this large basement kitchen, to which he now conducted them, entering by a back outside door. The aspect of the room under the ruddy glow was most welcome, and they gathered around the huge fireplace with great satisfaction. The day was cold; the sky, which, though clear in the morning, now began to be overcast with heavy clouds, and the damp chill atmosphere betokening a heavy storm. At David's request, Seeley was dispatched with an ox-team and sled to bring their bundles from Mr. Gunn's barn. This was accomplished without difficulty, a quantity of hay being thrown over them, under which they were effectually concealed from notice. Though Mr. Wooster's guests now felt themselves measurably safe, they were far from being at ease. The presence of the captive was a restraint upon them all. He knew nothing as yet, beyond his vague suspicions, of the business in which they had been engaged, and they wished, of course, to keep him in ignorance as long as possible. At length David bethought himself of the dairy-room behind the chimney, at that season of the year little used, as a place at once secure and remote from hearing; and at his suggestion, Chauncey was sent in thither, a stool being given him to sit on, and the big oaken latch of the door fastened on the outside, so that it could not be raised by the string from within. It was an admirable place of detention, where, without being subjected to personal violence, he could be kept with absolute security. Feeling now free to converse, the story of their expedition, so far as they chose to give it, was related to their host, and their packs having arrived, they were opened to show the booty they had obtained. David, disregarding prudential considerations, ran up stairs to show it to his mother. The rich goods – silks, linens, laces, etc., – elicited much admiration, and were freely distributed between Mrs. Wooster and her daughters. There seemed to be no misgiving on their part as to the mode in which they had been obtained. Dayton, they all said, had been a thief himself, and if he now lost his goods in the same way he got them, it served him right. No doubt he would make up the loss in the next piratical cruise, and more too. It was now noon, and dinner was prepared for the

party in the basement. Mr. Wooster brought out,

from the old-fashioned buffet in the corner of

the front room, a square bottle of West India rum –

This suggestion, however, was at once negatived by Mr. Wooster. It might, he said, do for them, but it would be fatal to him and his family. He had done enough already to bring down upon him the vengeance of the rebel laws, both as an accomplice with burglars, and as privy to and a helper of their intended flight to the British lines, which the legislature had made a felony. No; they must take the lad with them, and put it out of his power to testify against them. Some time after all these things should be settled by the ending of the war, he might, if he was still alive, be permitted to return home. Those considerations prevailed, and the idea of releasing Chauncey was abandoned. Graham, however, was not satisfied. He had nothing to fear from the release, for he expected soon to be out of the reach of the rebels, any way, but he greatly disliked the thought of taking the lad with them. He would be a restraint and an annoyance in their movements, and a constant source of danger. All the goods that Dayton had would be easier to carry than this one tell-tale Yankee boy. At length, during the temporary absence of their host from the room, Graham, in a low voice, but with a tone betokening both disgust and impatience, exclaimed vehemently,– A resolute man exerts an influence upon others greater than the intrinsic weight of his words. Graham was such a man, and when thoroughly in earnest, rarely failed of carrying his point. He was older than most under his leadership – perhaps forty-five. A native of Ireland, he had resided before the war in the south, where he first joined the American troops under General Moultrie. He was daring and ambitions and eagerly sought promotion in the army, to which his talents and services, as he thought, justly entitled him. At the same time he was jealous and easy to take offense; and having on one occasion failed to receive the meed of advancement which he coveted, in a fit of anger he foreswore the patriot cause, deserted to the British, by whom he was transferred to the army at New York, where he received a lieutenant's commission, and, as we have seen, was employed in the recruiting service on Long Island, and in the vicinity. He was a man of some address, and from his age and experience, as well as from his military rank, which was held in great honor in those days, he commanded, for the most part, the ready deference of those under him. So now his forcible statement of the necessity of the act proposed, together with his taunts and threats, began at last to work conviction in the minds of his present comrades. Several, indeed, persisted in opposition, but this only made him the more determined. He jeered at their scruples, he ridiculed their soft-heartedness, as he called it, declaring they were milk-sops and jelly-bags, with numerous other epithets far from complimentary, and set off with expletives of the choicest Satanic vocabulary, till at last, silenced, if not convinced, they desisted from their opposition, and yielded their assent to his proposal. |