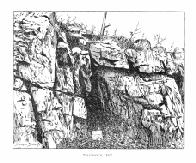

Chauncey JuddDayton's Den About a mile and a half west of David Wooster's

is a naked bluff of rock, the extremity

of which breaks into a jagged precipice overlooking

the valley below. By some geological convulsion

its strata have been raised into a nearly vertical

position, and, having fallen a little apart, they

open into several seams and crevices, the largest of

which is of sufficient width to admit a man. A few

feet from the entrance at the bottom is a cross crevice

of about the same lateral dimensions, which, extending

in a tortuous passage upward, affords an outlet at

the top of the ledge. Whether the place had any

particular designation then, we do not know, but at

present, by a similar confusion of names, it is known

in that region The woods into which the robbers fled, after their departure from Mr. Wooster's, extended along the slope of the rocky eminence all the way to the den, and by keeping themselves within the thicket, they reached this hiding-place unperceived. It was not a very comfortable retreat. There was barely room enough to stand within the crevices, and being situated in the eastern face of the cliff, it was exposed to the bleak wind blowing from the northeast, with the coming tempest in its breath. But its lonely position, remote from any road, and so elevated as to command a view of all approaches to it, gave them present safety. They dared not make a fire lest the smoke should betray them, but gathering a few dry bushes, they stopped the entrance so as partially to exclude the wind, and waited for the night, which would permit them to pursue their flight. Near the foot of the hill below the them – perhaps one hundred rods distant – lived another of the prominent tories of the region, named Noah Candee. He was a coarse, rough man, and one of the most violent of his party. His house was a favorite resort for persons of that faith, and many a scheme of treacherous villainy had been plotted under his roof. He was a blacksmith by trade, and besides his farming operations, was accustomed, especially in the winter, to work in his shop, where the teams of the neighboring farmers were brought to be shod, their ox-chains mended, their axes relaid, etc. Such a place, almost as much as the village tavern, became a center of news. The rumors that were afloat as to the war, the measures of the Congress at Philadelphia, the depreciation of the currency, the hard times, and all the usual sayings and doings of the town were detailed and commented on by the idlers and loafers, who loved the cheerful fires of the forge, and, above all, the cider which he was as generous in dispensing as he was in imbibing himself. To the refugees in the rocks the minutes moved on leaden wings. Cooped up in their inconvenient quarters, and shivering with cold, they were in anything but an amiable mood. Finally, Graham suggested that one of them should venture down to Candee's, to give him information of their whereabouts, and see whether there was not a place of concealment in his house more comfortable than the bleak cave where they then were. Nobody was willing to encounter the peril. After a little wrangling over the matter, however, Scott volunteered to go. The rest, from their elevated lookout, were to keep watch, and if the pursuers were seen approaching the house, a signal should be given by hanging one of their hats on a stick thrust into one of the crevices of the rock. Cautiously the scout descended the hill towards Candee's, skulking along behind the trees and fences. As he drew near the house, he heard the sound of the anvil in the shop, and concluding that Candee was there, he passed on to the rear of it, and after examining the interior through a crack in the boards, ventured to enter. As it happened, nobody was in the shop but Candee himself, and one of his tory neighbors, named Daniel Johnson. He had been down to the bridge in Judd's Meadow that afternoon, where he had learned of the events which were exciting that region, and had stopped at the shop, in passing, to relate the news to Candee. The two were engaged in discussing the affair, and calculating the chances of escape for the robbers, when Scott made his appearance.

Johnson also promised that he would keep a sharp lookout in the neighborhood, and as soon as it seemed prudent, he would come or send to them, and help them to find a shelter at his own house, or somewhere till the storm was over. So saying, he mounted his horse and rode away. Thus warned, Scott left the shop and succeeded in regaining his comrades without having been discovered. But he was not a minute too soon, for he had hardly disappeared in the woods before a large party were seen, down the road, approaching the shop. Of course Candee denied all knowledge of the persons inquired after. He was sure, he said, that they had not passed his shop, as he had been at work there all the afternoon. But his word was not sufficient. His character was too well known as that of an unscrupulous tory, and they proceeded to search his house and barn, but of course without success. After they left Candee took a bottle of liquor in his pocket, and went to his barn, ostensibly for the purpose of foddering his cattle and putting them up for the night. But this task having been completed, he cautiously went up the hill, keeping himself out of sight of the house, in the range of his barn, to the assure them. His liquor, however, was received with great satisfaction. He advised them to stay where they were till after dark, and even then to wait for word from Johnson or himself as to when it would be safe for them to move. After searching Candee's premises, the pursuers continued their course as far as Johnson's, whose house they treated in a similar manner. Finding, however, no trace of the fugitives, they concluded they had not come in this direction, and most of them returned to prosecute their search northward, toward Middlebury, and also in the direction of Waterbury Center. They, however, left persons at both houses, to watch the tories and guard the roads, with instructions to let no one pass who could not give a good account of himself and his errand. It was now a good while after dark, and the snow was falling very fast. As soon as he dared, Mr. Johnson set forth to fulfill his promise to the refugees. Without much difficulty he evaded, in the darkness, the eyes of those on guard, and taking a circuitous route over the hills and through the thickets, arrived at the den just as the men, grown impatient from waiting, were about to sally forth, and trust to their speed and their guns for escape. His arrival, therefore, was timely, and after finishing the liquor which Candee had brought them, they seized their luggage, and set forth, under Johnson's guidance, on the same circuitous route by which he had come. Not till they had passed some distance beyond his own house did they venture upon any road, and then, telling them to be silent and vigilant, he bade them good night, and returned home. Having now got out of Gunntown, they believed

themselves no longer in danger of immediate pursuit,

and followed the open road along |