Chauncey JuddRescue and FlightThe robbers, who had been waiting for Henry in Wooster's barn, became impatient at his failure to give the signal which had been agreed upon. It was already growing dark, and they were getting exhausted with their hunger and cold. As the storm abated there was more passing in the street, and several persons were seen on horseback, who, they suspected, might be engaged in the search for themselves. At last the suspense became too great to be borne. It was evident either that Henry had, proved false to them, or had been himself arrested, without an opportunity of giving them the signal by discharging his pistol. They determined therefore to wait no longer. As soon as it was dark enough to give them some feeling of safety, they slung their packs upon their shoulders, and seizing their muskets and halberds, made directly for Captain Wooster's house. Approaching it in the rear, they examined the kitchen through the window, and finding nobody there but the negroes and one whom they took to be their missing comrade, they opened the door and walked in. Their arrival, it may be believed, was most welcome

to the prisoner. In a word he had told them what

had happened, and was as speedily released from his

bonds. Tobiah afforded them no chance to retaliate

for the indignity, for he had departed, the moment

they appeared, to call help. Mrs. Wooster, hearing

the noise in the kitchen, came in, and forgetting the

prudential considerations upon which she had before

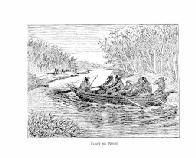

acted, counseled the party to flee forthwith. Language can but feebly portray the mingled transports of anger and fear which these words awakened. Famishing as they were, they felt that they must not delay a moment. The cider pitcher stood on the table near them, and one of them seized this and drained it of its contents. Then opening the door, without staying even to say good night, they crossed the brook and laid their course through the fields in a circuitous route by the way of Great Hill, for the Landing and the Island. Scarcely had they got out of sight before Tobiah and Peter returned with several persons whom they had chanced to meet that were already out in pursuit of the criminals. Foremost among these was Captain Bradford Steele, one of the most prominent citizens of the town, and a zealous patriot. He learned from the negroes the particulars of the arrest and rescue of Henry Wooster, and the advice their mistress had given them as to their flight. Others presently came in, and after a brief consultation, it was resolved to set forth in pursuit, gathering by the way as many as possible to join them. The race was now fairly begun. The robbers had the advantage of a few minutes' start of their pursuers, but the latter were, many of them, mounted on horseback and able to outstrip the fugitives in speed. The snow was in many places badly drifted, as it is apt to be in March, and the clouds, still lingering after the storm, covered the sky with a pall of gloom. This, however, was welcomed by the fugitives, as it aided them in concealing their course. That night march was one of the most formidable character. The extensive ridge of high lands, which may be regarded as a continuation of the Beacon Mountain, extending south-westwardly to the Housatonic and beyond, from which the name of "Great Hill" was derived, was then, for the most part, a wilderness, covered with woods penetrated by Indian trails and lonely paths known only to those dwelling in the vicinity. Henry and David were familiar with the locality, having often traversed it in hunting, and were enabled to guide their companions through the intricacies of their course. The direct distance from Captain Wooster's to the Landing is about six miles; but the circuitous route taken by the robbers must have been nearly or quite as much again. Onward they sped in silence, with every sense awake to their danger, and with loaded muskets ready to defend themselves if attacked. After traveling two or three hours they found themselves utterly exhausted, and coming to a clearing in the woods, where was a hut and a small barn adjacent, they crept into the latter in the hope of getting a little rest. They were not, however, able to sleep much, and after struggling an hour or two more with cold and fatigue, they set forth again on their flight. At length the morning began to dawn, and the weary fugitives found themselves within sight of the Landing at Derby. Hastening forward, they crossed the Naugatuck by the old bridge, where the road from Great Hill still passes, a little below the village of Ansonia. It was but a short distance from this bridge to the house of Daniel Wooster, uncle of Henry and David, Jr., which they had hoped to reach in season to obtain something to eat before setting out for the Island. But the unwelcome light of the morning rendered this unsafe, and it only remained for them to press on in their flight as fast as possible. At that time the Naugatuck River, at and a little above its junction with the Housatonic, was much deeper than it is now. The diversion of the water from its natural channel, for the service of the mills at Birmingham, has allowed its bed to become partially choked with sand and debris. Here, under the high eastern bank of the stream, were kept the boats and small craft belonging to the village. This point was reached by tide-water from the Sound, in consequence of which the river was seldom completely frozen over, except in the severest weather. Just below the junction a ferry-boat was accustomed to ply, connecting Derby with the opposite shore, from which a road ran along the western side of the Housatonic to Stratford. Rushing down the steep bank of the Naugatuck, the robbers found an old whale-boat lying in the stream, partly filled with water. To wrench it from its fastenings, bail out the water with their hats, break open a boat-shed near by and steal a couple of pairs of oars, and push off into the open current, was the work of but a few moments. Graham and the Woosters were skillful oarsmen, and a few vigorous strokes sent them out into the broad waters of the Housatonic; and just as the first rays of the sun shot across the lofty hills that embosomed the stream, they rounded the rocky point called the "Devil's Jump," projecting from the eastern shore, and laid their course down the river toward Long Island. Meanwhile the pursuing party had followed as rapidly as the night permitted. It was impossible to keep their track during the darkness and along the obscure paths they had taken, but their general course was rightly conjectured, and Captain Steele and his company hastened forward, hoping to intercept them at certain points which it was believed they, must necessarily pass. They, however, missed their aim in this respect, and just at dawn, as they approached the village, they again discovered traces of the robbers in the path. They galloped rapidly forward, crossed the bridge, and as they came down to the Landing had the mortification of perceiving the objects of their pursuit just going out of sight beyond the bend in the river below. For the moment the pursuit was arrested, and a consultation was held as to what should next be done. The news of the flight soon spread through the village, and a large number gathered to join in the chase. After a delay which seemed an age to the impatient

pursuers, the sleepy ferryman was aroused, and transferred

them to the opposite shore, where they set off

at full speed on the road to Stratford. But the fugitives

had started first, and did not fail to use the advantage

to the utmost. Both wind and current favored

them, and under the powerful strokes of the

rowers they made good speed. The whale-boats, of

which theirs was one, were specially constructed for

swiftness. The distance from Derby along the river to Stratford is fourteen miles. About a mile below the Landing, the stream makes a considerable bend toward the east, and is divided by a long, low island, then covered by bushes. This, with the wooded banks of the river, concealed the boat from sight, and the pursuers. having the shorter distance across the chord of the arc, actually got in advance of the robbers before the latter had completed the detour. On discovering the position of things, these halted under a thicket on the river bank, where for the time they were entirely lost to view, and it became a question with the pursuers what had become of them. The latter, however, continued on to the tavern, which was then known as the "half-way house" to Stratford, near what is now Baldwin's Station; and having had no refreshments since the preceding evening, they concluded to halt there for breakfast, first stationing sentinels by the river side to give notice if anything was seen of the boat. For some reason, however, this duty was but ill performed, and while the party were at the table in the tavern, the fugitives came silently and swiftly down the stream, in the shade of the opposite bank, and before the alarm was given had already shot by the house, and were leaving their enemies behind them. Instantly the pursuers were notified, and the race began anew. The road henceforth passed along the high grounds at some distance from, but in full view of the stream and the fugitives, who clung as closely as possible to the further shore. It was an exciting scene for both parties. The whale-boat was leaky, and required constant bailing to keep it from filling. There were only four oars for the whole party, poor ones at best. One of these, even, was for a while disabled by the breaking of the thole-pin. There were no means of replacing this on board, and they did not dare to stop to procure another. One of the men, however, bethought him of his bayonet, which he detached from the musket and substituted in its place. As it but ill-fitted the hole, Chauncey was ordered to grasp the socket and hold it firmly, and in this way it was made to serve as a point of support for the oar. There is a tradition, also, that two others of their guns were similarly fastened on either side of the boat, and that one of the silk gowns stolen from Mrs. Dayton was stretched across between them as a sail. But despite their utmost exertions their pursuers, now increased to a large party, gained upon them, and it seemed an even chance which should reach the Point first. Here, however, the river was broad, and the boat, still clinging to the eastern bank was inaccessible to those on the shore. As they passed the Point, they were hailed by some of the foremost and ordered to stop; at the same time several shots were fired at them, which the distance rendered ineffective. The only notice taken of these was a loud hurrah from the boat, accompanied by one or two return shots; when, emerging from the river, they came upon the waters of the Sound, and were soon far beyond reach.

|